(Re-post) Freeride Mountain Biking and Rhythm Sections - Reflections on ELEMENT#1

Originally posted on weallfalldown.dance/blog (now defunct) on 12 November 2021.

This article was originally published in Dance Nucleus’ magazine, FUSE#1, in 2018. Here it is shared in a heavily revised and updated form.

ELEMENT#1 was the point at which ideas that had been niggling at the back of my mind emerged from the miasma that is my brain and began taking shape in rough form. The work done during the residency has, over the course of three years and some, led to A Reason for Falling, a contemporary dance solo presented as a 35-minute long video installation at VECTOR#1, produced by Dance Nucleus in April 2021. Read more about it here.

Watch this video, and then this one They’re both videos of the winning run of the 2017 edition of Red Bull Rampage champion, Kurt Sorge.

Watching Rampage made me cringe and fret, grimace, plain ol’ freak out, and then finally drop into a state of mind-blownness trying to comprehend what the athletes, these artists with their mountain bikes, were doing. It’s nerve-racking just to watch, but the riders navigate on their vehicles terrain most people wouldn’t want to walk at speed, navigating gravity and aerial acrobatics with apparent ease.

What is Rampage?

Red Bull Rampage is a competition that celebrates a movement practice called freeride mountain biking (FMB for short). The event begins with riders and their respective teams spending ten days crafting out of the canvas of a mountain in Utah a line for the riders to descend; pathways that are judged on the elements of risk and difficulty, while the riders are weighed by their speed, style, and the tricks they execute.

The FMB that is performed at Rampage belongs to the wider umbrella of of action sports. Freeskiing, freeride snowboarding, freerunning, and on into wingsuiting, BASE jumping, freestyle longboarding or aggressive in-line skating or… the list goes on. And while these are all distinct disciplines, they share a common thread: taking what is known and matching that with a desire to forge new paths, push boundaries and discover possibilities. As Mike Gervais, a peak-performance psychologist quoted in The Rise of Superman puts it, “There’s a natural urge to compare athletes to athletes, but trying to compare a guy like Shane McConkey to a guy like Kobe Bryant misses the mark entirely. It’s almost apples and oranges. McConkey’s got more in common with fourteenth-century Spanish explorers than anyone playing on the hardwood. You want to compare these athletes to someone, well, you’ve got to start with Magellan.”

Freeriding in its variety of incarnations is, in other words, a pursuit of freedom.

And it was evident, from the first few minutes of Rampage, that in their exploration of the notion of freedom, the riders in the event were stretching the boundaries of what was humanly possible. Take, for example, the image below. How many of us would dare to walk or run down such a path? And yet, the freeriders cycle down these gnarly, high exposure pathways at speed - not forgetting the flips, spins, and style that are part of the package.

Rhythm Sections

While watching Rampage, one particular phrase the commentators kept bringing up caught in my mind: rhythm sections. A tight sequence of jumps or obstacles, too close together to allow for any mistakes on or between a feature, a slip-up in a rhythm section would be the end of a competition run. A blunder in such a section would mean that a rider would have to stop, or risk falling off or running into a cliff.

(For examples of rhythm sections, watch this video of Rampage 2017 at the following marks: 25:15, 32:44 and 1:44:45.)

And I began to wonder what it’d be like to be to dance along the edge of a cliff… but more practically, I also started to consider what a rhythm section in dance could be: what would it mean to have movements strung together in a way that meant a successful execution would be irrecoverable in the event of a slip, a trip, or a mental glitch?

By boiling the idea down into three key elements, the exploration began.

One movement must necessitate the next.

The need for continuous movement.

The need for the audience to know when a mistake happened.

It very quickly became evident that unlike a mountain, a dance studio or a stage don’t quite force one movement into the next. With the promptings of gravity being more or less equal across a flat space, virtually any movement can lead into another, as long as my technique could keep up with my ideas. Strike one.

(To gain further perspective on how much the landscape at Rampage shapes what a rider can do, watch this video of the Red Bull Rampage 2017 course.)

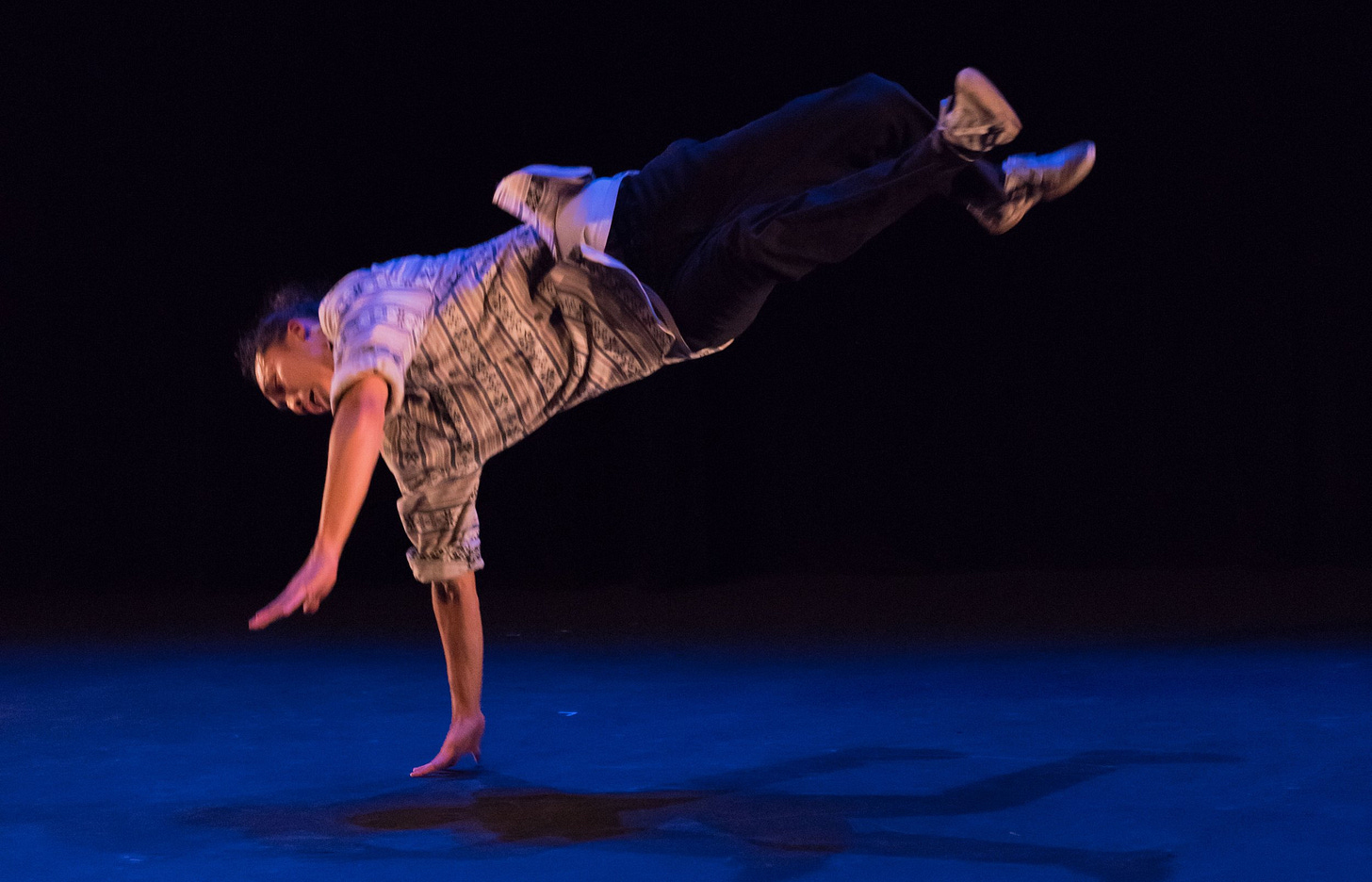

The second condition - the need for continuous movement - was at first glance a fairly straightforward condition to fulfill. After all, how hard is it to spiral and curve from one movement into another, since contemporary dancers, b-boys, and trickers do this all the time? Take away any sharp edges, and sudden changes of direction, and you can go on and on and on. Recording myself in rehearsal quickly revealed that it wasn’t that simple, though. More than continuous movement, what was needed was a persistent displacement of my centre of gravity. After all, Rampage and any other FMB competition isn’t about rider on bike flailing arms about like a crazy person. This would require more thought.

The third condition, the need for an audience to understand when a mistake happens, is pretty counter-intuitive. After all, who wants their audience to know that they failed? And like the first condition, the landscape of a dance studio or stage allows for mistakes to be disguised in a way that a Rampage run doesn’t. No hiding this accident, Nicholi Rogatkin. But, maybe it’s not about just letting the audience know whether or not I messed up. Perhaps what’s needed is to help the audience understand what’s at stake, so like in a good movie, the audience ends up caring about the success of the protagonist. I.e., they care to see me not fall flat on my face. Unless they’re sadistic, but that’s another story.

Arco’s Mentorship

Originally from Germany and now based in Brussels, Arco Renz is a choreographer who, in my words, specialises in taking movement vocabularies that are new to him, breaking them down to find their component elements, and then putting things back together in a way that uncovers new perspectives and possibilities. We spent a week together in March 2018, working at Dance Nucleus (Singapore) under the organisation’s ELEMENT#1 residency programme.

During this time, one of the key things Arco shared was how in his own choreographic processes, he began by searching for the basic state of existence of an idea, the mode in which a concept exists. In the case of Rampage, Arco saw this to be a spinning wheel, the thing that enabled a rider to progress down a mountain, the fundamental building block for all that made up any incarnation of freeride mountain biking.

Finding such a state is a way of crafting a performer’s mindset in order to inform the physical choreography. Finding an appropriate state of existence leads to appropriate responses to stimuli, whether these be conceptual prompts, music, directions in an improvisation score, or anything else.

(For more on Arco Renz’s work, see kobaltworks.be.)

So, Down the Mountain and On To…?

It’s been pointed out that FMB (and its rhythm sections) is but one of many possible ways of engaging with gravity, with falling and flight. And while freeriders find this engagement in the mountains, I find it on the dance floor, and in my practice of The Art of Falling.

In short, The Art of Falling is a practice that deals with learning how to enter and exit the floor. Beginning with the simple and practical, it grows to include the complicated, dynamic, and performative. And like freeriding, it’s a navigation of gravity, and a search for possibilities that lie in engaging with the limitations gravity imposes upon us.

How can these things come together? Can ideas from freeriding be brought into my own practice, to create a choreographic language, and works for stage? Can being in the zone, finding the flow state that drives so much of the progression in freeriding, facilitate a merging of ideas to unlock a new world of possibilities?. (For more information on the flow state, see the work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi or Steven Kotler.)